In the early '50s, there was a boat-building boom in Detroit. The effort was indirect response to the accomplishment of Slo-mo-shun IV, which in 1950 took the Gold Cup to Seattle. The Detroit contingent was rebuffed in'51 by Slo-mo-shun V and again in '52 by the IV.

Emerging as the leader from the east was Joe Schoenith, owner of the Gale racing team. Schoenith's plan of attack for'53 included a new boat, Gale III, U-53.

"It was built in '52 and finished in the winter, " Joe's son, Lee, remembered in a 1984 interview. "The design of the boat was as close to a copy of Slo-mo-shun as we could come. The big innovation in that boat was the fact it was a single engine, twin propellers. "

The new Gale was designed by Lyle Ritchie, the Schoeniths' crew chief. It was built under Ritchie's direction by Leonard Helpke, according to Lee. The boat's gearbox was the focal point of interest. "It was a gearbox that bolted on an Allison. It had two shafts come out of it; one turned right hand and one turned left hand," Lee explained. Ritchie hoped the counter-rotating propellers would eliminate torque. A single rudder was mounted to the center of the transom, between the propellers. Topside, the cockpit had two seats.

Gale III sported other technical features that drove its cost skyward. Exhaust stacks, probably water cooled, ran through the hull and out the transom. The need for two shafts and two propellers made the III one of the most expensive hydros of the 1950s. Les Staudacher in a 1976 interview said, "I think probably that was the most expensive boat the Gale people ever had built . . . Boy, they spent dough on that boat."

Had Gale III been a costly success, the financial sting may have been easier to bear. Unfortunately, it was one of unlimited racing's most expensive failures. "The boat never did run too well," Lee Schoenith admitted. The December 1953 issue of Lakeland Yachting put it this way: "Talking to Joe and Lee Schoenith of the famous Gale racing boats, we found them not very happy about the final results of their Gale III, which was new this year. They figured it would be about the fastest thing afloat, which it wasn't." Mel Crook (Yachting February 1954) was no kinder: "Gale III — she of the twin surfacing props — is reported to have missed expectations. A new Gale IV is nearing completion."

Gale III made its first public appearance at a sanctioned event October 24-25,1953, during mile straightaway trials on Lake St. Clair. The Gale, with Lee Schoenith driving, joined Such Crust III and Such Crust V. Officials on hand included R. A. "Dick" Leavall, timer, and Gibson Bradfield, president of the American Power Boat Association. Wind and snarly water scrapped the attempt. "It was rough, and nothing ever happened," Lee Schoenith remembered. The only boat to attempt a run was Such Crust III, with Roy Duby driving. The shaft bent, and the effort was aborted.

Because Gale III made so few public appearances, photos of it are extremely rare. Richard Degener, an outboard racer who at the time lived in Grosse Pointe, Michigan, was a spectator at the straightaway run. His photographs of the boat at the Grosse Point Yacht Club are the definitive portraits of the III in its earliest configuration.

The Gale III was tested on the Detroit River again in April 1954, but results remained unsatisfactory. Gale IV and Gale V, both new for that season, carried the team's colors into battle while the III waited at home. During the next three years, Gale III was seldom mentioned in print, and it never went to a race. "We always had another boat — the Gale IV, the Gale V — that was much better," Lee Schoenith noted.

The May 1954 issue of Lakeland Yachting and the July 1954 issue of Motor Boating both reported the Schoeniths were giving thought to converting the boat to a conventional power train with a single shaft, but no reliable reports exist to confirm that they ever did so. One account said the Schoeniths were considering the III for a role as a publicity vehicle, so Joe Schoenith could take business clients and friends for rides on the Detroit River. It never happened, although the report of Joe Schoenith as a driver proved prophetic.

Gale III made only one other appearance at a sanctioned event. It was entered in the'57 Detroit Memorial. To the horror of his attorneys and accountants, Joe Schoenith qualified the boat for the regatta. (It was subsequently withdrawn, possibly because a suitable driver could not be found.) At the time, the Schoeniths were in the midst of a legal battle with the IRS over the status of their racing equipment. After Joe Schoenith toured the Detroit River course, IRS attorneys claimed he was acting out of love for his hobby rather than as a businessman using the sport solely to promote his business. It became a pivotal argument in court when the Schoeniths lost their tax case.

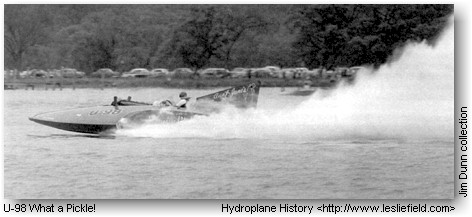

Following the Detroit Memorial, Joe Schoenith sold Gale III to Gordon Deneau, who re-named it What a Pickle! The boat returned to the Detroit River in September for the Silver Cup still wearing the number U-53. Later it was renumbered U-98. With Deneau driving, the Pickle was sixth in the Silver Cup and eleventh at the President's Cup. The craft was last every time it ran; its best heat speed was a little over 76 mph. Walt Kade handled the boat in the Rogers Memorial at Washington, D.C.. He was unable to complete heat 1B, which turned out to be the Pickle's last run.

Deneau never finished paying, and when the '57 season was over Joe Schoenith took it back. A few years later Lee Schoenith burned it and four other hulls.

Gale III is a fabled boat in unlimited history for several reasons. First, it has a lineage in one of the sport's most famous racing teams. Second, it was built with unique features and remains a technical curiosity. Finally, it appeared so rarely and photos of it are so scarce that the craft is shrouded in mystery. Some unlimited historians regard it as the lost Gale.

The willingness of some owners to innovate and experiment with hull design, powerplant, and power train has made unlimited racing a sport filled with better mousetraps as well as Titanics. For every Slo-mo-shun IV, there's a Gale III; for every U-95, there's a Miss Lapeer; for every "Blue Blaster" Atlas Van Lines, there's a four-point Miss Circus Circus. Unlimited racing's history is enriched by its flops almost as much as by its advancements. The Schoeniths deserve credit for trying with Gale III. There's no shame that it was unsuccessful; over the years, they had many other accomplishments for which they were justifiably proud. If Gale III had worked the way it was intended, one can only guess what modern unlimiteds would look like.

(Reprinted from the Unlimited NewsJournal, March 1999. Used by permission.)

Hydroplane

History Home Page

This

page was last revised

Thursday, April 01, 2010

.

Your comments and suggestions are appreciated. Email us at wildturnip@gmail.com

© Leslie Field, 2000