|

|

Pop Cooper — 225 Speed King [1940] |

|

|

The Pop Cooper Story |

Pop Cooper — 225 Speed King

[1940]

|

It was the afternoon before the Rockledge regatta down in Florida last winter and Jack Cooper was providing some bits of action for the benefit of the newsreels. He was bouncing along at 70 m.p.h. when, suddenly, he felt the steering apparatus go limp in his hand.

His craft wavered an instant, then headed straight for a concrete abutment built out into the water. Cameramen kept right on shooting. Less than fifty feet of water separated the nose of the boat from the concrete wall; a spectacular smash-up appeared inevitable. It was curtains for the driver.

The newsreels didn’t know their man. As soon as he sensed the danger he rose up in his seat, cut the ignition and hopped into the water with only a second or two to spare before the crash. Cameramen winced when they heard him hit the water, yet he managed to get to a pick-up boat unassisted and, an hour later, the dunking all but forgotten, he was helping a carpenter put some temporary planks on the bow of the damaged waterbug so he could race it the following day. And race it he did—and won.

|

In the light of this disclosure, you’ve probably pictured Cooper as a brash, slam-bang youngster without a care. But this is not quite accurate, for actually he’s an unassuming little man of 126 pounds who looks like a book-keeper and who enjoys dangling his grandchild on his knee when he’s not away at the racing wars. What’s more, he’s highly unsalty, hailing from out on the edge of the wheat belt where, even in the years when farmers aren’t buying their water from Sears-Roebuck, he’s got to pack his boat a couple of hundred miles before he can find a suitable stretch of water for taking a practice spin.

Pop’s his nickname and no one’s ever bothered to ask him his age. It’s determined largely on geography. Along the grapefruit circuit, Florida sport writers seldom report him to be under 75, so his performances will serve as a psychological tonic for the rocking chair fleet that gathers there in winter. When he’s competing in Canadian and eastern regattas his reported age fluctuates between sixty-five and sixty-nine, occasionally seventy—when a feature writer wants to strengthen his story.

Cooper gets a belt out of seeing his age change from week to week and in his spare time likes to speculate on what the attitude of the press would be if the word ever got in circulation that he’s only a stripling of sixty.

But disregarding his age, Pop is king of speed and champion excitement provider in a sport designed strictly for those who never tire of the stomach-in-the-mouth sensation. A barber pole has no more color than this white-haired, leather-faced driver, and no matter where he goes the crowds pull for him as if he were a home town boy.

|

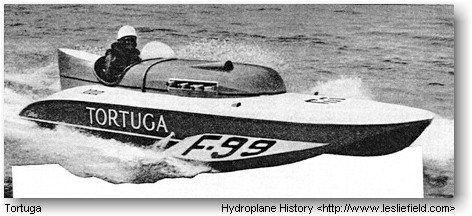

He races in the country’s most popular in-board racing division, the 225 cubic inch class, that being the piston displacement of the craft’s motor. With his blue and white speedster and its two predecessors, Tops I and Tops II, he’s been shattering records since 1937, and as far as silver trophies and plaques are concerned he’s got enough of them stacked away at his home in Kansas City to preclude a shortage of that metal.

A few years back, when a 225 driver, Dr. R. C. Hermann of Cincinnati, scampered over a stretch of Florida water at a speed of 59.172 miles an hour, this mark was expected to stand for years. But the following season at Red Bank, N. J., Pop erased it by becoming the first hydroplane pilot to crouch behind the steering wheel of a 225 cubic inch craft and push it to a speed of more than a mile a minute.

Of course, some of the larger boats, the Gold Cuppers and the Harmsworth trophy contenders, had gone faster, but such a pace in a craft built to the minimum of 15˝ feet on the water line and 4˝ feet of beam, and with a motor limited to 175 horse power was undreamed of. The competition grew keener. Whenever someone beat his mark, he’s striven to hang up a new one—and so far he’s been successful. It’s a dangerous way to play—a skid on a turn, a floating log, or the wash from a larger boat crossing the course—all these can lead to serious consequences, but Pop thrives on excitement. Right now, he’s the owner of three world’s records and your banker, if he knows his way around in racing circles, will let you have money to bet Pop will annex a few more before the season has spent itself. And, possibly, the top spot in the national rankings for hydroplane drivers, though this honor is of no importance to him. Speed, not championships, is what he’s after.

The less hullabaloo there is accompanying his performances the better he likes it. On his Canadian junket last summer, for instance, he decided to try for a new mile straightaway record at Picton, Ontario. Thousands would have turned out for the event except for the fact that Pop set about the chore at 6 o’clock in the morning.

Sunrise on the course, the Bay of Quinte, is a glorious sight, but its beauty escaped Pop that morning. He was too concerned about the weather. "When you’re going for a record," he points out, "the water’s got to be right. Not too calm nor too choppy. On a rippleless surface there’s what’s known as skin-friction between the water and the bottom of the boat, and this has a tendency to slow the boat up, just as rough water does. A gently rippling surface—that’s what the script calls for."

The procedure on a non-competitive mile test is this: Two successive mile runs are made, one going one way, the other back over the same route. Times are taken on the each and the official reading made from the average speeds of the two.

On the outward run, a cross-wind caused the hydroplane to leap crazily into the air and two or three times it came within a fraction of capsizing. Nevertheless, his official speed for the first mile was 87.379 m.p.h. and with no prankish cross-swell doing tricks on the return trip, he was clocked at 87.591 for a general average of 87.485 — an improvement on the old world’s record of nearly two miles per hour.

Pop made a clean sweep in Canada’s major meets, plucking off the Canadian National championship and the British-American oil trophy in straight heats. An American team picked by him raced against a crack squad of Canadians in an international match at Muskoka Lakes and he finished first in every event. The eastern and New Jersey championships, too, were just a breeze for him and when the Circuit Riders gravitated to Detroit for the running of the 27-mile race for the W. D. Edenburn trophy he was in top form. As is true of most, the Edenburn is awarded on the basis of points scored in each of 9-mile heats, 400 for first, 300 for second, 225 for third, 169 for fourth, and 127 for fifth.

In the first heat he finished fifth, but came back strong in the second to capture first honors while posting a new 9-mile record of 66.639 miles an hour.

Accordingly, when the seven boats in the race lined up for the final 9 miles around the 3-mile course, Pop and his two favorite competitors, George F. Schrafft and Tommy Chatfield, all stood a chance of winning. With a first and second, Schrafft had 700 points, Pop was next with 527, and a second and third gave Chatfield 525.

Racing enthusiasts of Detroit — there were more than 50,000 of them on hand — will long remember the pulsating thrill of that three-way duel, how Chatfield in his Viper III jumped into the lead with a well-timed start and how he kept it throughout the entire first lap. At the beginning of the second three miles, however, Tops III moved to the front but dropped back to second where Chatfield’s superior speed forced him to remain until the final turn at the last lap. Pop started gunning his motor for an extra ounce of speed, got it—and slipped home ahead of the other two by barely three lengths.

In Florida this year, the Kansas Citian began making a name for himself just as he’d done in 1939. At Lakeland, where’s he’s done a deal of mark making, he traded in his old 5-mile competitive record on a new one — 68.650 m.p.h. But this one’s career was short lived, for in the following heat, just thirty minutes later, he was officially clocked at 70.810 m.p.h.

The water was choppy at Palm Beach and Tops III’s blunt nose, the aftermath of the Rockledge incident, took a terrific beating, but it won the 225-class race and, moving on to Bradenton, repeated its success.

Some of Pop’s other Florida starts, though, were packed with more grief than a day-time radio serial.

Look what happened to him at St. Petersburg.

Before you do, let’s get the picture on the start of a speedboat race. Five minutes before race time, a gun is sounded, a red flag raised. Four minutes later, there’s a second gun shot and another flag raised, this time, a white one. Also, the giant time clock is started and the red flag is withdrawn. Sixty seconds tick off and the gun is fired again, the white flag is dropped—and the race is on.

The top flight driver times himself so he’ll cross the starting line right on the nose with the throttle wide open. He knows if he can beat the pack to the first buoy he stands a good chance of winning. But should he jump the gun or fail to approach the starting line properly he’s disqualified or the race is restarted.

On this particular afternoon in St. Petersburg, Pop was tinkering with his boat in the pits, located in a sheltered bay about a half mile from the racing course proper, and, apparently, did not hear the 5-minute gun.

As he was making a final check-up, one of the regatta officials went by and Pop hailed him, "How long before the gun?"

Presuming he’d heard the pre-race warning, the official replied, "Three minutes."

Pop didn’t hurry to get to the starting line, but when he was out about a quarter of a mile back of the course the gun went off and he realized his mistake. He saw Tommy Chatfield’s boat streak across the starting line, and in a flash he realized he’d have a substantial headstart on him. But Pop decided to give chase, anyway

One by one he overhauled the other boats. Only Viper III was ahead of him. The gap between them began to shrivel and at the final turning buoy, Pop edged into the lead

Kerplop!

A floating bottle struck Pop’s propeller. He eased his throttle — Viper III streamed by and on to win.

His boat was thrown out of balance and the attendant vibration began ripping a large hole in the bottom. Vainly he tried plugging the hole with his kapok jacket, but the boat sank lower and lower into the water. He beckoned for assistance from the pier and in order to keep the craft afloat until it could be made fast with a rope, he jumped into the water without bothering to put on his jacket.

In the heat of the excitement, a young millionaire sportsman dove in after Pop — a generous but unnecessary gesture; Pop had toyed with the idea of becoming a channel swimmer before he took up hydroplane driving.

For the past two seasons he’s ranked No. 2 in the national ratings and the only way he could land on top is by bowling over the major regattas as he operates a big motor car transport company out of Kansas City and can’t get away to pick up points at minor events. One of his few eastern appearances this year has been in the New Jersey state championships at Lake Hopatcong. He won six straight heats in the 225-class championship, but failed to retain possession of the Governor’s Trophy which he won in 1939 when a defective steering mechanism forced him out of the running.

The boat Pop races is not big as inboards go, but what he’s done in a few competitive races against Gold Cuppers with motors twice the size of his has provided much fodder for racing arguments. The men who pay from $25,000 to $50,000 for these 500- and 700-horsepower jobs are chagrined whenever they lose a free-for-all to Pop’s boat which cost less than $2500.

In the 1937 National Sweepstakes at Red Bank, N. J., Cooper showed his mastery at the wheel by beating two Gold Cup craft. Competition is open to any single motored craft regardless of size and the competing drivers abide by the rules governing their particular class.

That year 225-class pilots had a choice of driving either with or without mechanics, and Pop, as is his wont, decided to ride alone in the first heat and won it handily.

On the second day of competition, Gar Wood flew into Red Bank and asked Pop if he couldn’t accompany him. He agreed, but later regretted it, not that the Silver Fox’s company wasn’t agreeable, but simply because the extra 130-pounds of weight cut down his speed nearly a mile and a half an hour, which was just enough to give Jack Rutherfurd, piloting his 320-horsepower Ma Ja II, a victory in a heat.

Riding alone in the finals, Pop was out to win. The crowd realized he wasn’t going to have an easy time of it, for behind the wheel of the second Gold Cup, Miss Palm Beach — nee Miss Columbia — was Mrs. Maud Rutherfurd and it was only reasonable to suppose she’d show a fine sense of family pride by helping her husband bottle up the upstart at first opportunity just as they’d succeeded in doing so beautifully the day previous.

Sensing their intentions, the veteran driver got off to a beautiful start and was well down the straightaway before Ma Ja II crossed the line. Rutherfurd barrelled his motor and by degrees came within hailing distance of Tops II.

It became evident that Miss Palm Beach was no match for the two and dropped back, leaving Pop and her husband to battle it out alone. Around the 2˝ mile course they streaked 65 m.p.h.—a dizzy pace, and one the crowd did not think the smaller craft could maintain over the full route. Right at its stern Ma Ja II stayed, gaining a little on the straightaway, dropping back on the turns where Pop was doing his stuff. Every time he rounded a buoy the crowd gasped. Either his eyes were going back on him or he was deliberately trying to come as close to the markers as he could without scraping off their paint.

The final lap. On the back stretch Rutherfurd was almost up to Pop and on the inside. There was a chance of his pulling the race out of the fire by swinging wide at the turn and cutting in. Rutherfurd did swing out, but that was as far as he went. His boat swerved as if it were going over. He eased up on the throttle. Keeping to the outside and with his motor roaring like an army bomber, Pop beat him into the stretch and across the finish line by two-fifths of a second, to receive an ovation that would make even Joe DiMaggio grow pensive. Both boats eclipsed the previous mark for the distance, which gives you an idea of the pace.

One of the best stories told on Pop happened at the President’s Cup regatta at Washington a couple of years back.

There was a trim craft bearing the title Smyne that took Pop’s eye before the race. It was the boat he’d have to beat. Having a 650-horsepower motor, it showed Tops II its wash on the straightaway, but this was more or less counteracted by Pop’s generalship on the turns. The race was almost a photo-finish, but Pop was the winner. After he had slipped off his jacket and helmet he stepped to the judges’ stand to receive the cup and be introducd to his opponent, John Charles Thomas [a well-known opera singer of the time —LF].

In making the presentation, Thomas philosophized, "At least, I can beat him singing."

"It’s a bet." came back Pop, laughingly.

Speedboating is one of the rightful heritages of youth and how Pop weathers the mental strain, tension, and ceaseless pounding of the rock-ribbed water is a matter of wonderment.

You’ve heard of the hell-diving that’s done in this sport. If you haven’t, it’s the equivalent to being tossed by a bucking bronc and once a driver takes a spill he’s supposed to lose some of his daring. Some have even been known to develop a cautiousness which, in hydroplaning, is fatal. Not so with Pop. He’s taken as many spills as any driver in big-time competition, yet continues to disport himself as if he had ice water coursing in his veins.

A crack-up written indelibly on his mind occurred at Palm Beach two years ago. As is the case generally when something is about to happen, Pop had the event in the bag and was homeward bound when his boat thundered into a piece of driftwood. Over went Tops II — and Pop with it. The shock was absorbed to some extent by his crash helmet and life-jacket, but he could feel the effects for several days. He came out of this one much better than the boat, the hull of the latter being reduced to kindling wood, and by the time the motor was extricated from the bottom of the course it was badly damaged.

Speed’s not Pop’s only distinguishing mark. At a meet he’s easy to pick out in a crowd as he wears glasses, taped to his head and protected by a celluloid visor on his helmet. Only once have they given him trouble, two years ago at Toronto during a race he still can’t think about without first calling for a pillow.

"That race," he told us in his Kansas City office recently, after his secretary had brought him a cushion, "was the damndest race ever run.

"Something told me we were all crazy to go out in that wild, choppy water and I was sure of it when, before we’d hit the first turn, one of the boats, scudding along in the wash of a leader, bounced over a wave, hit another, and then turned over. A few minutes later, another one that had been leaping out of the water like a game fish took two flips and struck the water bottom side up. And that wasn’t all, another that was coming in for repairs tangled with a swell and sank in forty feet of water."

The boats finishing the race were so badly battered a crew of boat-builders had to be hired to work all night to get them in shape so they could start the second day.

In the nightcap, the water was a little calmer, but Pop, who was being held together by bailing wire and arnica, wasn’t up to any struggle. He quietly got in behind one of the more intrepid drivers so he could have the water smoothed out for him. Everything went fine until the trail blazer churned up a heavy spray and Pop, flying on his instruments, so to speak, ploughed into a turning buoy.

Pop likes to tell of the time in Detroit before the 1938 races when an elderly man came up to him in a boat-yard and began asking him questions about his boat, how fast it’d go, how much the fuel cost, and the way in which races were conducted.

When Pop had finished answering his questions, the man said, "I’m going to get me one."

"What for?" Pop asked.

"To race—what do you think?"

The man looked to be in his late seventies, so Cooper tried to explain that he was too old to take up inboard racing, but the old man wouldn’t hear of it. "You talk like my wife," he said. "But wait — I’ll show you both."

Pop didn’t hear any more about the old man until Arno Apel, his boat builder, wrote him he’d received an order from a man 79 years old named Robert Jaite, of Jaite, Ohio, who said he wanted a boat that was fast enough to beat "Cooper’s Tops II."

Sure enough, when Pop looked over the starting line-up in the Prince Edward Gold Cup race at Picton, Ontario, last summer, there was the man with whom he’d talked in the boat yards behind a slick new craft called Apache.

Cooper was the defending champion and when he won the first heat it looked as if he were the class of the race. He was surprised to see Apache come in second.

"In the next heat," recalled Cooper, "I was doing 72 m.p.h. and going for a world’s record. As luck would have it, a battery cable worked loose at the fag end of the race and short circuited. I slipped in a new one and managed to get in fourth.

"But, of course, you know who was first That’s right, Jaite." Pop won the final leg of the race with Apache coming in second. Jaite had him beat on points. At the cup awarding ceremonies, Pop says he could detect a gleam in the winner’s eye that was meant just for him.

The barnacled background of the Kansas City driver dates back a decade or so to Gull Lake, Minnesota, where during his summer vacation, he first tasted the thrills of the sport by skirting around the lake in an outboard at 12 miles an hour.

This palled on him after a time, so he took up outboard racing, won the first event he entered — after the three others in it had capsized.

Four years ago his interest was transferred to the speedier 225-class hydroplanes. He cut quite a figure in the puddle regattas his first year but found the going rough in the larger meets. Upon his return the year following he proved to be a sensation, winning not only at Red Bank in the National Sweepstakes and the 225 championship but also in Louisville, Boston, Toronto, and Washington, and taking second place at Cincinnati.

Under the present design and racing conditions, 90 m.p.h., he feels, will be the limit for 225’s over the measured mile and that the present crop of drivers are not likely to exceed the 80-mile an hour limit under competitive conditions.

The Coopers are the Barrymores of speedboat racing. Son Thom, who’s Class A champion in the outboard division, manages to carry off chunks of the prize money in three of the lighter classes. Pop’s daughter Nellie set a world’s record in the midget outboard class before she retired from competition. Young Jack is coming along as a 225 driver and now Nell’s husband, Hud Weeks, is breaking in as an inboarder.

Pop’s toying with the idea of retiring. Aviation bug’s been biting him and he thinks it would be fun racing the clouds.

Faster, you know.

(Reprinted from Motor Boating, September 1940)

Hydroplane

History Home Page

This

page was last revised

Thursday, April 01, 2010

.

Your comments and suggestions are appreciated. Email us at wildturnip@gmail.com

© Leslie Field, 2005